by Rex Rowan

1. Pioneers: Frank Chapman, T. Gilbert Pearson, Oscar Baynard

2. The University: Charles Doe, Robert McClanahan, J.C. Dickinson, Oliver Austin

3. Birding: 1957 to the Present

1. Pioneers: Frank Chapman, T. Gilbert Pearson, Oscar Baynard

If we leave out incidental observations by botanist William Bartram, who visited the area in 1774, the history of bird study in Alachua County goes back a little over a century to November 22, 1886, when Frank M. Chapman (1864-1945) arrived in Gainesville.

He had lately resigned his post at the American Exchange National Bank of New York to come south for relief from respiratory problems – Gainesville had a reputation as a health resort – and to begin “the business for which I came here,” his ornithological studies.

At the time, Paynes Prairie was at the bottom of Alachua Lake, and remained so until 1891. Chapman described the lake as “about nine miles long and averaging two or more in width. A large portion of its surface is covered with a dense growth of yellow pond lilies, locally known as ‘bonnets,’ affording a home to innumerable Coots and Ducks. At its eastern end is an immense savanna bisected by an inflowing creek, and dotted with clumps of cypresses and numberless small pools. A few years ago Herons were abundant and bred here; today it is comparatively deserted, the result of merciless persecution by plume hunters.”

Chapman explored several spots in the area, including Bivens Arm, Sugarfoot Prairie (north of Lake Kanapaha), and Newnans Lake, but spent most of his time at Alachua Lake. His first description of it is memorable: “There was a splashing and calling, a squeaking and squawking such as I had never heard in my life before, odd noises of all sorts and descriptions all unknown to me. The place seemed to be alive with birds, ducks were constantly flying from place to place, coots and herons were apparently common. On the shore near me birds were just as abundant; a pair of Pileated Woodpeckers with flaming crests were pounding away in a tree above my head and with them were hundreds of Flickers and one Red-bellied Woodpecker. Doves whistled through the woods at my approach, Bluejays screamed, Mockers chirped and hundreds of birds flew from tree to tree. Truly I was in an ornithologist’s paradise.”

Not all of Alachua County struck him quite that way. A journey of several days west of Gainesville elicited the following words: “the country is dreary and desolate beyond description, an unending forest of pines with nothing to disturb the monotony of the scene.”

When he went back to New York in late May 1887, Chapman had recorded 149 species of birds in Alachua County and secured 581 specimens. He went on to become one of the most respected naturalists of his time – Curator of Ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History, pioneer in Neotropical ornithology, author of what was for many years a standard reference, Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America, and founder of both the Christmas Bird Count and Bird-Lore magazine, which later became Audubon. But one of the first published works of this distinguished career was an 11-page paper in the Auk for July 1888 entitled, “A list of birds observed at Gainesville, Florida.”

Conservationist T. Gilbert Pearson (1873-1943), though born in the Midwest, lived in Archer from 1882 to 1891.

He was a 14-year-old bird enthusiast and amateur oölogist when he met Chapman for the first time; many of our more interesting nest records date from his youthful explorations, the results of which he dutifully reported to his hero. He eventually traded his egg and skin collections for tuition at Guilford College in North Carolina and went on to a productive career as, among other things, President of the National Association of Audubon Societies (1920-35).

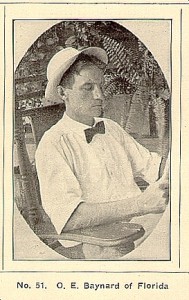

As mentioned above, plume hunters were quite active in the area, well into the early years of this century. The Audubon Society employed a succession of wardens to keep them away from the colonies at Bird Island in Orange Lake. Oscar Baynard, the first of these, served from 1911 to at least 1913.

He was so effective – Bird Island was the only successfully-protected nesting colony in the state – that he could with justification boast, “There are probably more Egrets in [Alachua County] than in all the rest of the State and with the vigorous protection that they are now receiving here it is hoped that they may be the means of repopulating the State with this showy and valuable bird.”

He was an enthusiastic oölogist, and his field work, mainly around his Micanopy home, resulted in, “Breeding birds of Alachua County, Florida” (Auk, April 1913), a paper containing, among other things, this poignant note: “Campephilus principalis. Ivory-billed Woodpecker.-Very rare. Found one nest in the county that contained young. Fresh eggs about February 15.”

(Oh, to be Oscar Baynard!)

2. The University: Charles Doe, Robert McClanahan, J.C. Dickinson, Oliver Austin

Although the University of Florida was founded in 1853, it wasn’t until 1917 that the Florida State Museum was established around a core of specimens obtained from a Lake City community college.

Initially, malacologist Thompson Van Hyning ran the whole show himself. Not merely a mollusk biologist, Van Hyning was a mollusk enthusiast – I confess I have some trouble imagining this – who named his children after mollusks (!) and, upon his retirement as director, backed a truck up to the museum, loaded a good portion of the mollusk collection into it, and drove away. He wore long black coats and celluloid collars, and looked, according to J.C. Dickinson, “like a hellfire and brimstone preacher.”

The museum’s first “bird man” was Charles Doe, a coal dealer from Providence, Rhode Island. He was also an oölogist whose feverish devotion to his hobby drove him to raid nests by moonlight when he couldn’t get out during the day. Doe had a rich patron whom he chauffeured to Florida every year, and in 1931, in return for a generous donation, the patron succeeded in arranging a place for the 68-year-old Doe and his egg collection at the Florida State Museum (quite an achievement, considering how little there was to the museum at the time: for years the entire staff consisted of Van Hyning, Doe, two secretaries, and a janitor). Doe was a tireless collector, in the field almost every day during the nesting season. Most of the egg dates in “Birds of the Gainesville Region, Florida” are taken from the extensive collection he assembled at the museum. (Another reason he spent so much time afield: he and Van Hyning hated each other, so much in fact that Doe eventually moved the bird collection to P.K. Yonge School.)

It was during Doe’s tenure that Robert C. McClanahan came on the scene. McClanahan, an education student at the University from 1930 to 1934, had been a protege of Francis Weston’s in Pensacola. After receiving his degree, he returned home, where he taught at Pensacola High School and issued several papers having to do with the birds of both Alachua County and the Pensacola area. Most interesting of these to us is the “Annotated List of the Birds of Alachua County, Florida,” which appeared in the Proceedings of the Florida Academy of Sciences in 1936. Fifty years previously Frank Chapman had recorded all the birds he encountered during a six-month stay, and in 1913 Oscar Baynard had listed the county’s breeding birds, but this was the first effort anyone had made to enumerate all the birds of Alachua County – the breeding birds, the wintering birds, the migrants, even the accidentals. Drawing on Chapman’s and Baynard’s papers, personal communications with Baynard, and his own experience, he came up with a list of 190 species (compared with 343 in 2007). After this McClanahan worked for the Biological Survey and wrote several more papers on Florida birds, the last of which (1941) noted the first specimen of Franklin’s Gull in Florida, which he had collected at Lake Okeechobee. He enlisted following Pearl Harbor and died in the course of military service in 1943.

Doe left the museum in 1940-41, Van Hyning in 1946 (with the truckload of mollusks, remember), and for a time after the war the collections languished. A part-time employee kept the door open for the public, but there was no curation or administration. In 1952 a committee was appointed to determine whether to get rid of the collections or revive the museum. They voted to revive, and hired J.C. Dickinson as Curator of Biological Sciences on a part-time basis.

Dickinson had first come to Gainesville as an undergraduate in 1934, and did graduate work in ornithology as Pierce Brodkorb’s first doctoral student. He comments that, during his tenure, the “bird collection never amounted to much.” When he became director full-time in 1957, he called old friend Oliver L. Austin, Jr. and invited him to apply for the job in the bird collection.

Austin was the museum’s first full-time ornithological curator. He came to the museum from a military background: during the American occupation of Japan, he served as chief of the Natural Resources Branch’s Wildlife Section, reforming Japanese hunting and wildlife conservation laws and putting an end to market-hunting of birds. Some market-hunters caught songbirds with nets of fine, almost invisible, mesh; Austin saw the possibilities for utilizing these “mist nets” in bird-banding, and introduced this useful tool of field ornithology into the United States.

When Austin came on the scene, he immediately began to build up the collection, and the museum drawers filled with specimens, including a great number of local ones. Opinions diverge in regard to killing birds for science, but the study collection for budding ornithologists would have been pretty poor if he hadn’t been such an enthusiastic gunner. He apparently did little research, spending most of his time on editorial activities – the Auk, journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union, was under his direction from 1968 to 1977, and he put together the last installment of Arthur Cleveland Bent’s Life Histories of North American Birds. In addition, he authored Birds of the World, a popular coffee-table tome illustrated by Arthur Singer.

David W. Johnston, compiler of the recently-released Birder’s Guide to Virginia, was an active researcher and even more active collector during Austin’s tenure. An avid field man, he confirmed the first county nestings for the Northern Rough-winged Swallow and the Indigo Bunting, commemorating the latter with, “Ecology of the Indigo Bunting in Florida,” in Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences in 1965.

By 1973 Austin was ready to step down. He telephoned J.W. Hardy at Occidental College in Los Angeles. “I’m retiring. You want a job?” he asked. In contrast to Austin, Hardy collected few skins and skeletons, discouraged by complicated legal restrictions. Instead he collected something else: sound recordings. Hardy had become interested in bioacoustics at Occidental, and had established a library of natural sounds there in 1962. Upon his arrival at Florida he immediately instituted a new sound library, on which he has worked ever since, gathering voices of birds from around the world. It is the second largest such collection in the New World in numbers of species, exceeded only by that at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Beginning in 1977, with the publication of “Voices of Neotropical Birds,” his company ARA Records began to publish the best of this collection on record and tape. He continued this work even into retirement.

David Steadman, an avian paleontologist from the New York State Museum in Albany who had done graduate work at UF in the 1970s, took over curatorial duties in 1995 upon the retirement of Dr. Hardy. He began expanding the skin and, especially, skeleton collections to include material from South America and the South Pacific.

In addition to work associated with the museum, which in many instances has had little to do with local birdlife, contributions have been made by graduate and undergraduate students in the zoology and wildlife biology programs. These did not begin until the late 1930s; prior to this, the school was almost entirely an agricultural college, and all the graduate dissertions from the first one of 1909 until about 1936 had to do with cultivated crops (lots on citrus) and insect pests. Many of the student contributions have been of a technical nature – J.C. Dickinson’s review of the towhees, for instance – but many have been of more general interest, for instance Bartley J. Burns’s “A survey of the birds of Newnans Lake, Florida” (1952), David O. Karraker’s “Birds of Lake Alice” (1953), and Donald A. Jenni’s “The breeding ecology of four species of herons at Lake Alice, Alachua County, Florida” (1961). In fact, some of these field studies have served as sources of information nearly as valuable as the works of Chapman, Baynard, and McClanahan.

3. Birding: 1957 to the Present

I now come to that part of the history possessing the most immediate interest for us: the era of birding pursued as a hobby. Or not exactly a hobby: John Hintermister distinguishes between a.) birdwatchers, and b.) people who put their lives on hold in order to bird. Our cast of characters generally falls into the latter category.

John, for instance. Born in Gainesville in 1943, he was a small boy when two regular winter guests at the White House hotel, which his father managed, began to take him along on their birdwatching excursions to Lake Wauberg, Lake Alice (“a fabulous place in those days”), Micanopy’s Lake Tuscawilla, and the open water of Paynes Prairie – at the time a cattle ranch owned by the Camp family – which had more water and a lot more birds than in recent years (“It was incredible. There was a huge heron rookery there. There was a huge open spot to the west, and there were ducks up the gazoo!”). By the time he was 11 he was hooked: he and his brother, with orders to be home by lunchtime, would pedal to Lake Alice, “and we would get a hundred species … Now I don’t know that we identified them correctly, but we had a hundred species!” They may well have identified them correctly; upon seeing a bird, the boys would stop and read aloud the entire description from the field guide!

John didn’t know it, but he was riding a trend. Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds, which went through two editions and several printings upon its publication in 1934, became so much more popular after World War Two that in 1947 Peterson brought out a third, revised edition. That same year saw the publication of the first issue of Audubon Society Field Notes as a separate publication.

Field Notes (also known as American Birds from 1971 to 1993) had been a regular column called “The Season” in Audubon magazine since 1917, but with the booming popularity of birding it quickly outgrew its allotted space. In the first issues (1947-48) the reports of Pensacola’s Frances Weston were the only ones given for Florida, but as time went on researchers in the Everglades, and especially Henry Stevenson of Florida State University, began to beef up the state’s seasonal accounts. However it wasn’t until 1965 that Gainesville’s academic researchers, particularly David Johnston, began to send in information. And it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that Gainesville’s amateur birders began to submit regular reports.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Although local Audubon Societies had existed in several Florida cities, both large and small, since the 1930s (e.g., Jacksonville, Winter Park, Coconut Grove), Alachua Audubon did not come into being until January 11, 1960. Among its charter members were Oliver Austin, J.C. Dickinson, Jr., environmentalist Marjory Carr, and 16-year-old John Hintermister. The first year’s field trip schedule included River Styx, Lake Alice, the pinewoods north of the airport industrial park (where Red-cockaded Woodpeckers nested), Lake Tuscawilla, “the Arredondo quarry,” the Devil’s Millhopper (not surrounded by housing developments then), Cedar Key, Seahorse Key, Paynes Prairie, and San Felasco Hammock (the latter two still private property at the time).

In those days – through the 1970s, in fact – the National Audubon Society sponsored a series of nationally-touring nature films shown each month during the winter at the Reitz Union or Gainesville High School; these were Alachua Audubon’s “program meetings.” Roger Tory Peterson was a regular on the tour, and when he visited, every two or three years, University Auditorium was booked to hold the crowds. On one of these occasions, John remembers, he handed his field guide to Peterson to be autographed, and Peterson held the tattered, well-used volume aloft and commented, “This is the way I like to see them.”

And even before Alachua Audubon there were Christmas Bird Counts. Mary Sherwood led the first, in 1957, in which six birders put together 16 party-hours and saw 74 species. Although she missed 1958, she was back in 1959 with a dozen birders. The CBC has come off annually ever since – the 2000 Count was the 43rd.

Christmas Counts were a little different in those days. From 1962-70, as coordinated by Austin, they began at first light and ended at lunchtime with a tally at Archie Carr’s Micanopy home. There were no assigned territories, no team captains, no organization of any sort. Participation was meager at times – in 1962, Austin’s first year, there were only two parties, and they put in a total of 12 hours. The number of people participating never rose above 25 between 1957 and 1973. Results, likewise, were meager: species totals between 1959 and 1970 ranged between 94 and 123 – in contrast to the years since 1971, in which they ranged between 126 and 148.

But to return to our hero. After enjoying the customary distractions of youth – in his case these included duck-hunting, often on Paynes Prairie (“Mr. Camp ran me off so many times he finally said, ‘Just don’t shoot any of the cows, boy.'”) – John married in 1967 and settled down to begin his best birding years. At first he and Caroline Coleman were about the only real birders (see definition in first paragraph) in town. John remembers telling his wife, “You know, I’ve been out birding for three months, and I have not seen another birder.” But that soon changed.

In fact, it was during the years 1968-71 that what I might call Alachua County’s Golden Age of Birding began. “There were a lot of good birders and everyone was enthusiastic,” John recalls. “There weren’t a lot of weirdo birdwatchers then, people just looking for the list.”

Through the Christmas Bird Count John met whiz kids Jimmy Horner, 11, and Bob Wallace, 12, to whom he became mentor – and chauffeur. “I hauled those kids all over the damn world,” he remembers. “They were enthusiastic birders. Those boys had some eyes, too. They could spot everything.” And in 1971 Steve Nesbitt arrived to work at the Game Commission, young and eager (John would ask, “When are you going on the Prairie?” and Nesbitt would reply, “I’m going right now if you want to go!”). Their sightings littered the Florida reports in the newly-renamed American Birds.

Coincidentally, it was in 1971 that Austin gave up his position as compiler of the Christmas Count and passed the baton to the younger generation. Al Stickley, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, took over. Stickley was the local American Birds correspondent, and an active field birder whose Big Day team set a record on May 1, 1971 of 125 species in one day in Alachua County, a record still unbroken.

Stickley handed the reins to John the following year. John made a few changes. He’d read in Peterson’s Birds Over America about the methodical way in which the Bronx CBC was conducted, and he sought to emulate it. He instituted dark-to-dark counts. He cut up a topographic map of the Count circle to make territories, and then went over each territory with a fine-tooth comb, appointing team leaders and assigning them important birds to find in their particular tracts. Under his leadership participation grew: after 1975 the number of birders enlisted never fell below 42, and after 1982 it fell below 60 only once.

(Incidentally, John was also responsible for the fact that Gainesville’s CBC is always on a Sunday; he was at the time manager of the Sears men’s department, and couldn’t get Saturdays off.)

Gainesville’s Golden Age was simply the local aspect of the Golden Age going on everywhere else. The atmosphere and adventure of this time has been captured admirably in Kenn Kaufman’s Kingbird Highway, which details a year the teenaged Kaufman spent hitchhiking back and forth across the continent in pursuit of birds. Irrational, adventurous things were taking place in Florida too. Big Years, for instance: in 1972 John Edscorn tallied 327 species of birds in Florida; two years later Lyn Atherton saw 347. The founding of the Florida Ornithological Society in 1972 brought all Florida birders together (though the first meeting, in St. Petersburg that April, was disrupted beyond recovery by The Mother Of All Fallouts at Ft. DeSoto). Florida birding involved a smaller, more tightly-knit group then, according to John. Look, for instance, at the list of participants in the 1973 Jacksonville CBC, and note how many top birders came from out of town to help out – Wes Biggs, Paul Fellers, Larry Hopkins, John Edscorn, Johnny Johnson, and Gainesville’s David Johnston and Jimmy Horner. John says he looks at ABA’s Florida List Report now and hardly knows anybody on it.

In 1974, a young couple named Jack and Jessie Conner moved to Gainesville to work on graduate degrees at the University. Jack developed a sudden and dramatic interest in birds – just how it happened, you can read for yourself in his book, The Complete Birder. John adopted the Connors. He loved Jack’s enthusiasm, and the two shared an interest in sports as well. The Connors became an integral part of Alachua Audubon. Jessie edited The Crane, while Jack wrote the “Birdwatching” column that Barbara Muschlitz inherited from him in 1979 and passed on to Mike Manetz in 1994.

The Conners lived on Lakeshore Drive near the crew team parking lot, and it was the birding they did around their home that brought Newnans Lake’s abundance of birdlife to everyone’s attention. In addition to the hot spots mentioned previously, most of which have continued to attract birders, favorite locations at this time included County Line Road, along the south edge of Lake Tuscawilla, and Ames Farm, in Jimmy Horner and Bob Wallace’s neighborhood off NW 23rd Street north of NW 16th Avenue (now a housing development, of course). The two miles of Paynes Prairie along US-441 was still a good spot, but the state had bought the Camp Ranch, the core of what is now Paynes Prairie State Preserve, in 1970, and in 1978 the Prairie’s main entrance was opened to the public. In the years between the purchase and the opening, Barbara Muschlitz remembers, “We used to die to go out on Paynes Prairie and we had to get a ranger to lead us on. And we’d think, this is Heaven.” Likewise San Felasco, obtained by the state in 1974, was opened to the public in the late 1970s.

Barbara had begun birding about the time the Connors arrived. She’d joined the Audubon Society some years before, hoping her subscription to Audubon would begin with an issue, devoted to hawks, that she’d admired at her sister’s house. It didn’t, but her membership included a subscription to The Crane, and there she saw that a field trip to Cedar Key was scheduled. Taking her son as a sort of human shield – she didn’t know anyone else in Audubon and was a little shy – she went along. On the way John pulled the auto caravan off the road to look at a Swallow-tailed Kite. This marvelous sight motivated her to start birding regularly. She went so far as to join the Christmas Count in 1975, and when Bob Oades, a visiting psychology professor from England, showed her an Ovenbird – a lifer for her – she began that association with our CBC that culminated in her being compiler and co-compiler from 1982 to the present day.

Alas, nothing lasts forever. The Conners finished school and went home to New Jersey in September 1978. The whiz kids grew up: Bob Wallace gradually dropped out due to competing interests in surfing and fishing; Jimmy Horner left town to begin a career. Things began to slow down.

In 1979 John quit Sears, spent a year building his house, then went to work at Morningside Nature Center. For a couple years he and Don Morrow taught birding classes and led Morningside-sponsored trips as far afield as the mountains of North Carolina. But this pleasant situation unraveled due to their boss’s failing marriage, and when a job came open with Steve Nesbitt in 1981, John took it. Working with birds eight hours a day drained his enthusiasm for watching them in his time off. And the preoccupation of getting a pottery business underway after he quit the Game Commission in 1982 left little time for it anyway. It was this withdrawal of Gainesville’s best birder from the scene that put a period to the Golden Age.

And when it was over, it was really over. Barbara was still going strong, but, as she writes, “Essentially, I was the only person birding actively in the 80s. I’d get people to go out with me. Some people came and went: Mike Resch, Dave Trochlell, Jay LaVia.”

It wasn’t dull all the time, though. In 1985 the Florida Audubon Society instituted the Breeding Bird Atlas project to map the distribution of Florida’s bird life. John was the original county coordinator, but when his son was born he handed the job off to Barbara. For the next five years, Alachua County was more assiduously surveyed than it otherwise might have been, and some valuable information was obtained; for instance, Reed Noss found Hooded Warblers nesting at San Felasco Hammock, something that had been suspected since the early 70s but never confirmed.

Then there were the Santa Fe Community College birding classes. John had begun them in the mid-70s, and resurrected them when he was at Morningside. Now the Alachua Audubon Society took them over, and they prospered during the late 80s and 90s. Kathy Haines, then Ike Fromberg, coordinated and taught, and managed to turn out at least a few good birders, for instance Mike Manetz.

When I arrived from Jacksonville in 1988, and despite Barbara’s low estimate of the birding scene in that decade, I was dismayed at how little my 14 years of experience signified by Gainesville standards. Barbara was actually intimidating (“Barbara, this is Rex Rowan. I saw a Painted Bunting today!” “Oh. Okay … Is that all? Okay, thank you. Bye.”). She and John, with their Alachua County year lists and their amazing discoveries, seemed to inhabit some unreachable pinnacle of accomplishment and expertise, and it was my great ambition to be taken seriously by them (any day now…). But they weren’t the only ones. On my first field trip, I met Carmine Lanciani and Karl Miller, and realized that what passed for a high level of birding ability on the Jacksonville scene didn’t count for much down here.

However, through the Santa Fe birding class I met Ike Fromberg and Jimi Morris, and with them I began to explore the area in earnest. Then, in 1992, I met a beginner named Mike Manetz who turned out to be some kind of birding genius, and the two of us began a frenzy of local birding that culminated, in 1995, with the publication of A Birdwatcher’s Guide to Alachua County, Florida(second, revised edition now available in a bookstore near you – new federal regulations mandate at least one in every home!).

Recently, when I asked him to reminisce about the Golden Age, John replied that the Golden Age is now: “There have never been so many great birders in the field at the same time.”

Sadly, John passed away in 2019. Read more about his contributions to birding in Alachua County here.